Build Public Renewables: When Less is More

Why Gov. Hochul's new offering of the Build Public Renewables Act is overall an improvement over the legislature's bill, despite preserving an essential flaw.

On February 1st, Gov. Kathy Hochul of New York released her new Executive Budget, a package of legislation that marks a starting point for annual negotiation with the state legislature. For the purposes of Public Power Review, the most interesting part — labeled with the enticing name "Part XX" (p. 289 here) — is her administration's version of the legislature's Build Public Renewables Act (BPRA), a bill that’s failed in the past two legislative sessions. BPRA would enable the New York Power Authority, a state agency, to enter the contemporary game of renewables development, in competition with the many private entities.

In short, Hochul's BPRA proposal is an improvement over the legislature's version and a win for public power. Moreover, it’s undeniably a product of the past few years of campaigning by a coalition of environmentalists, progressives, and especially socialists — and, very likely, of the recent passage of the Inflation Reduction Act. But it retains a fatal flaw of the original.

Last summer my collaborator Matt Huber and I wrote an op-ed for The Intercept offering substantive policy and political criticism of the original BPRA, from a socialist perspective. (Here I'll refer to the legislature's bill, introduced once more in the current session, as the original BPRA, in contrast to Hochul's BPRA.) The gist is that we supported it in spirit but the bill — in large part because of the composition of its coalition — had severe drawbacks technically and politically. Some of those drawbacks remain even in Hochul’s proposal.

But it nonetheless strips away most of the troubling elements of the original. What's left is a pared down bill that enables New York public power to enter a new domain of the economy — renewable energy technologies, developed and underdeveloped — without confining it entirely to that domain. It’s also a much-needed political mandate for the seemingly sclerotic institution of NYPA to act as the state’s active player in the game of electric power.

Whether this bill will meaningfully expedite the achievement of the state’s climate goals, as BPRA’s supporters have long argued, is another question.

To understand why the bill is an improvement over the original, let’s go through the strengths and weaknesses. As a caveat, I Am Not A Lawyer: these are my not necessarily legally sound impressions.

Empowering without Disempowering

The original BPRA would empower NYPA to build, own, and operate new renewable energy systems. That essential idea, certainly a positive political change, was captured in the name and campaign. But it also set a deadline, of 2031 in the latest version, by which NYPA could only operate and sell renewable energy. Hochul’s BPRA retains the former but tosses out the latter.

To a layperson, and certainly to a climate activist, requiring NYPA to divest itself of non-renewable resources might sound like a sensible strategic move to reach the state’s ambitious climate goal of 70% electricity generation from renewables by 2030. But in actual fact, this part of the original bill has always been technically and administratively unsound.

What would it even mean for NYPA to only operate renewable energy systems and only sell renewable energy? Would it involve the purchasing and retiring of “renewable energy certificates,” which is the international standard for adjudicating claims about renewability of power transactions, and which today NYPA generates none of? If NYPA were to build a new transmission line, how could one say it was only “for the purpose of […] transmitting renewable energy”? What would count as “excess renewable energy” and how would NYPA allocate this to new residential customers? Etc. These questions were never answered — and, it seems, rarely asked.

A more immediate concern is that NYPA owns and buys power from several different non-renewable, fossil-fueled generators in order to supply power to its (public) customers, like the New York City government and the MTA transit system. These generators also provide crucial reliability for the NYISO bulk power system, particularly in “Zone J”, the highly constrained load zone for New York City. There’s more to say about some of these generators next.

For as long as non-renewable resources are critical for the reliability of the electrical grid, we should not prohibit NYPA from owning and operating them — especially if older, dirtier, for-profit resources outlast them. It’s a simple public power principle, but one that is in conflict with the mindset, embodied in the original bill, that sees no technical impediments to an ever-increasing “percent renewable” figure.

Hochul’s BPRA additionally enables NYPA to sell power — from renewable sources only — directly to load-serving entities (i.e., to investor-owned utilities) and into the state’s power markets, two kinds of engagements in the economy that, it seems, have been much more circumscribed in the past. The latter in particular might help pay for new programs.

“Energy Justice” for NYPA’s Peaker Fleet

About those non-renewable NYPA generators. A topic I’ve long intended to write about for Public Power Review is NYPA’s fleet of seven peaker plants in New York City and Long Island. For two decades these “small clean power plants,” as NYPA calls them, have gotten a bad rap from the Green groups of New York City. Even Democratic Sen. Michael Gianaris denounced them as unnecessary on the State Senate floor, in the midst of making an otherwise admirable stand for public sector development in the power system with BPRA.

Installed in 2001 on an emergency basis, several months before a projected electricity shortfall in New York City, NYPA’s peaker fleet should be seen as a shining — though fossil-fueled — example of public power and direct state action in the economy. The state had determined that NYPA was the only entity, public or private, that could bring emergency generators online quickly enough.1 And indeed they did — building and operating them at cost, not for profit.

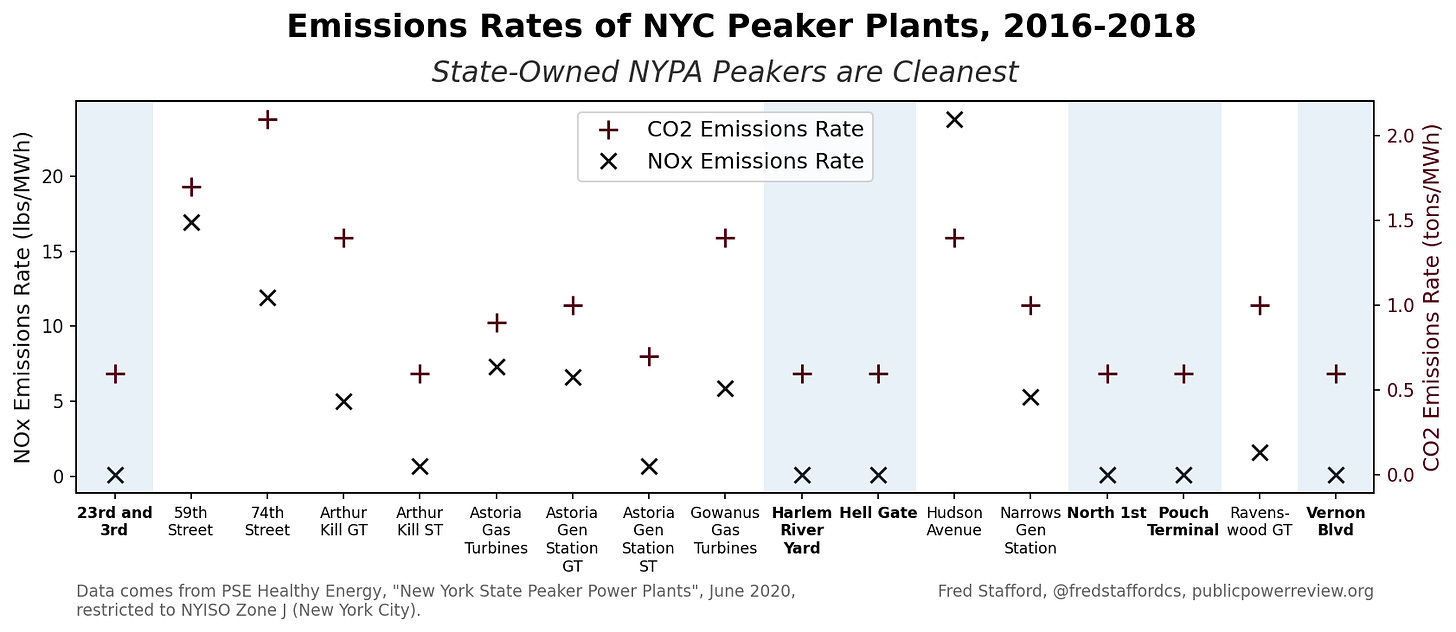

For these generators NYPA installed then-modern pollution control technology; performed the first environmental justice analysis by any New York State agency2; and modeled air quality against as-yet-not-finalized EPA regulations for particulate matter emissions, showing that even under the most conservative assumptions the plants would meet them.3 To this day, they are the cleanest peaker plants in the city by a wide margin, compared against the privately-owned peakers, as the following chart shows.4

NYPA’s peakers are so much cleaner than the others that replacing them with battery storage would increase emissions in the city. That seemingly counterintuitive effect was the projection of a study released last year by NYPA and the PEAK Coalition of Green nonprofits, a misfired attempt by the latter to force NYPA to replace the peakers with their preferred resource. Basically, swapping out the peakers for battery storage means increasing utilization of the much older, much dirtier competition.

The unfortunate reality of the power system is that natural-gas-fueled power generation will be with us, to hopefully decreasing degree, for many more years. The good news is that peaker plants like NYPA’s fit into the use case of flexibly ramping up and down based on need, an operational behavior that will prove critical as (intermittent) offshore wind begins to feed increasing amounts of power into the city in the coming years.

The current version of the legislature's BPRA mandates that NYPA rid itself of non-renewable assets by the end of 2031. But it allows such an asset to remain if NYPA publicly demonstrates an electrical reliability need and receives written approval from the local “clean energy hub.”5 What’s a clean energy hub? Each one is quite literally a nonprofit community organization picked and funded by the state … to help provide the state’s own services. Faced with yet another pitched political battle over fossil fuels, it could just be easier for NYPA to sell such an asset to a private owner in order to keep it running. That’s not unlike NYPA’s sale of its Indian Point Unit 3 nuclear plant, the largest privatization in the state’s history.

Hochul’s BPRA, on the other hand, does not require 100% renewable assets for NYPA. But more than that, it has a subsection6 devoted specifically to these peakers. NYPA must provide a plan for phasing them out by the end of 2035 (instead of 2031), but can decide unilaterally, in consultation with the NYISO grid operator et al., whether they should remain online for reliability. Even better, it specifically prohibits any replacements that would increase emissions in New York state or elsewhere — like those battery storage facilities that the PEAK Coalition wants.

The Public Sector Against Green Nonprofits

By tossing out the 100% renewables requirement for NYPA, Hochul’s BPRA surely upsets Green groups. But there’s another reason that these groups backing the original will be particularly frustrated: Hochul’s version drops provisions that would hand over explicit decision-making power and even some funding to them.

For example, consider the original BPRA’s requirement of sign-off from the local clean energy hub in retaining a fossil-fueled generator for reliability. In such a scenario, the state would be asking for permission from unelected nonprofit staff to maintain a critical resource for the city. More concretely, that person might have this exact job at the nonprofit serving as the clean energy hub for Brooklyn and the Bronx, seemingly granting them decision-making power over the fate of the majority of NYPA's peakers.7

The original BPRA would also have required various plans around climate resiliency and so-called “democratization” to be undertaken after multiple public hearings and after collecting input from all sorts of stakeholders and groups. In particular, NYPA’s plans “shall be created in partnership with […] a statewide alliance of community organizations” for whom NYPA would be “providing funding […] as necessary for their participation in the completion of the plan.”

Such community organizations already have their hands in the cookie jar of the state’s climate policies. Manhattan's clean energy hub and BPRA supporter WE ACT for Environmental Justice was recently granted $3.8 million from the state to carry out its hub responsibilities. That’s not as sweet as the $6 million grant they received in 2021 from Amazon owner Jeff Bezos’s Earth Fund. Another progressive nonprofit, PUSH Buffalo, is getting $3.5 million to act as Western New York’s hub. Both organizations have been vocal proponents of BPRA, and both have staffers appointed to lead the state’s official Climate Justice Working Group. The executive director of another BPRA proponent, UPROSE, also sits on that working group, and so does her husband, the executive director of the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance, also a proponent of BPRA. Perhaps it’s no surprise that these nonprofits already embedded in state policy-making support a bill to deepen their involvement.

Fortunately for anyone interested in building state capacity, everything about NYPA’s interactions with and dependencies on the world of nonprofit community organizations is dropped from Hochul’s BPRA. Outside of NYPA, however, the clean energy hubs remain a (still new) component of the state’s climate policies.

Thanks, Joe Manchin

Not so much an improvement over the original as an update, Hochul’s BPRA clearly bears the mark of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the federal legislation negotiated in secret by U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin and signed into law since the original BPRA last failed. The IRA’s “quiet revolution on public power” breaks decades of neoliberal renewable energy policy by enabling most public power entities to finally take advantage of federal subsidies.

The earlier ineligibility of NYPA to receive such subsidies was a key argument that Huber and I made last year: that renewable energy was cheap and that NYPA would be competitive with private developers was taken for granted by the original BPRA’s supporters. Thankfully, IRA levels the playing field.

And sure enough, new language in Hochul’s proposal gives NYPA new administrative and corporate capabilities — e.g., to “form or acquire interests in ‘special purpose entities’” — almost certainly just to capitalize on the world of clean energy tax credits now open to it.

Means-Tested Redistribution via Utility Bills

The original BPRA would make NYPA a supplier of residential end-use customers of (renewable) electricity, a fundamentally new role for the agency. Arguments from BPRA supporters that it would lower utility bills rested on a provision that “excess renewable energy” be sold to means-tested, low-to-moderate-income households at half the price their utility charges. Apparently, NYPA would produce renewable energy so cheaply, so ubiquitously, that it would be allocated to needy people around the state for half the price charged by the other guy. How this would pencil out for the agency was never divulged.

BPRA supporters have cited existing and past NYPA programs that offer businesses and nonprofit entities in the state cheaper power in exchange for job retention, like the Recharge NY program passed by Gov. Andrew Cuomo. But decades of such programs have always been predicated on NYPA’s cheap, firm hydro and nuclear power and on a rate design that ensures NYPA recovers the costs of that power — not a statutory promise of a 50% price cut.

Hochul’s proposal, however, replaces the price cut for excess renewable energy with a far clearer accounting trick. The REACH program — Renewable Energy Access and Community Help — would first create a pool of “bill credits” matching the renewable energy generated by any new NYPA projects and then fractionally allocate those credits to the program’s participants as literal credits on their regular utility bills.

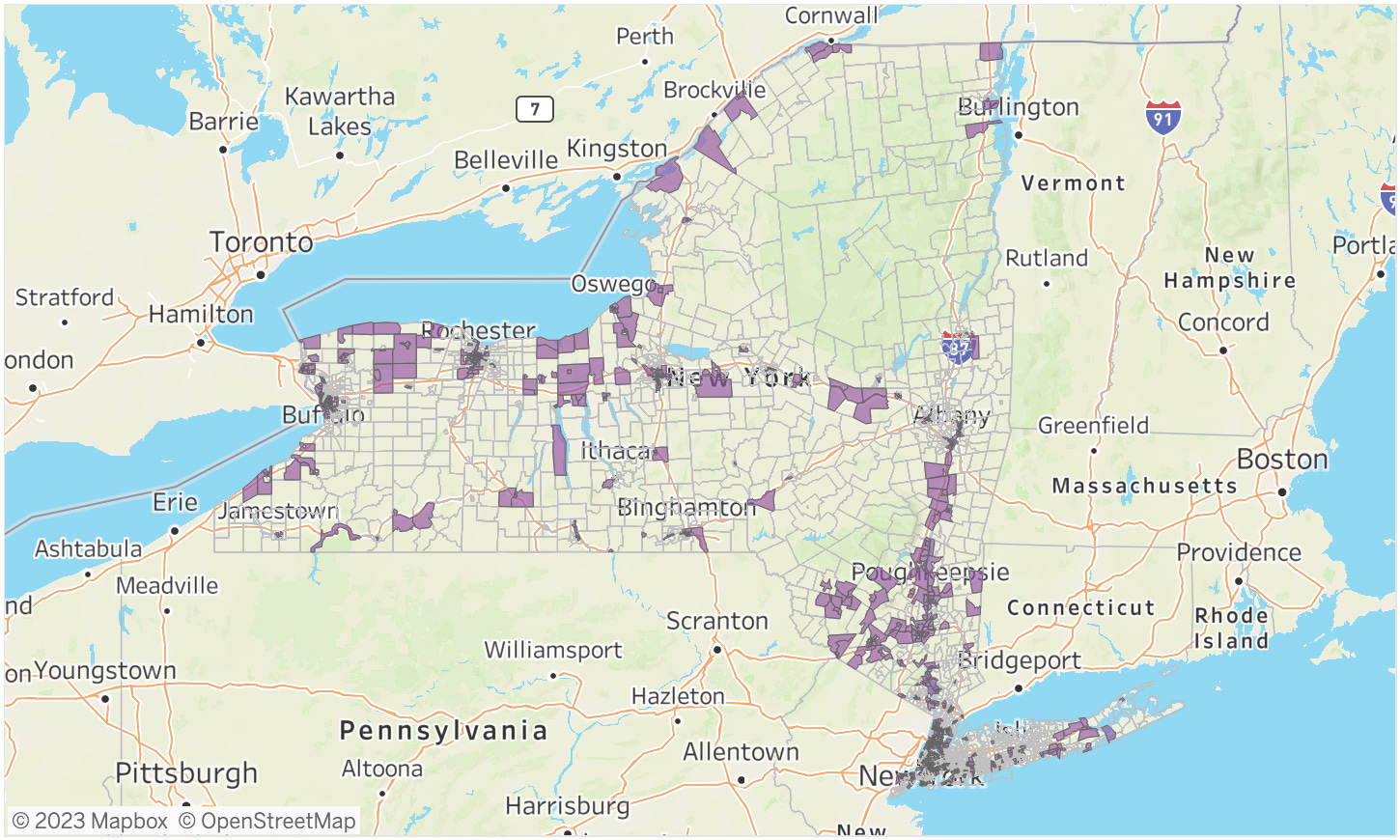

Who are these REACH participants who materially benefit from NYPA renewable energy then? “Disadvantaged communities,” a legal term enshrined into the state’s climate laws, defined with environmental justice metrics that are still being finalized. Currently it includes households living in the census tracts below and those earning 60% of the state median income.

How these bill credits for disadvantaged communities would pencil out financially is still a bit murky. But it’s at least clearer than the original BPRA’s magic 50% price cut: in Hochul’s proposal, the bill credits assigned to a utility’s customers would be funded in part by general NYPA revenues but also by new fees collected by that utility from the rest of their customers.8 It's redistribution, but using the more regressive "taxation" of utility bills rather than the far more progressive taxation powers of the state. But taxing the rich to pay for clean energy is a harder political lift than designing yet another utility bill reallocation mechanism.

That being said, pinning NYPA renewable energy projects to material benefits on people’s utility bills is a great way to rebalance the current political economy of renewables in favor of those who aren’t the lucky landowners (or the financial institutions harvesting the tax credits). But doing so only for means-tested recipients — “disadvantaged communities” deemed the objects of environmental injustice by impenetrable quantitative metrics — does not seem like such a popular political prospect.

Large-scale wind and solar projects in the parts of New York with available land are slowed and even defeated by local opposition. If a project is being proposed by NYPA rather than some fly-by-night developer who’s mostly there to help JP Morgan collect the tax credits, perhaps fewer people would oppose it. And if everyone in the locality received utility bill credits for it, surely more people would support it. That’s especially important given that NYPA does not pay property taxes to local governments, a fact that the private competition has been eager to play up. Unions agree with that concern too,9 and hope to see NYPA continue to make “payments in lieu of taxes” like they do today — but, unfortunately, aren’t required to by law, or by any BPRA proposal.

Instead of compensating the locals, both the legislature’s and Hochul’s versions of BPRA set their sights on means-tested benefits only. In our hypothetical NYPA project, imagine a local zoning committee meeting in which the room divides into the perceived givers, who would be charged fees by their utility to pay for the project’s bill credits, and the perceived takers, who would receive those bill credits. That’s a long way from the universal public good promoted by Franklin D. Roosevelt: cheap public power for everyone.

Weakened Labor Language, Not Weakened Labor Support?

The original BPRA contained multiple provisions that would enable organized labor to acquire and maintain a foothold in renewable energy work. If there’s an unequivocally negative departure from the original BPRA, it’s that Hochul’s proposal drops the specific provision requiring that any NYPA renewables project be considered “public work” that must be carried out with project labor agreements (PLAs) between contractors and labor unions, and with support for labor apprenticeships.10

It's possible that the state's existing public works law that requires PLAs and prevailing wages on clean energy projects — a law resulting from the efforts of a labor coalition that’s been notably absent on BPRA — would apply to new NYPA projects. That would appear to hinge on sales of renewable energy certificates to the state agency for renewable development. (Again, I Am Not A Lawyer.)

The lack of the original BPRA’s explicit language on PLAs and the public works law is a loss nonetheless, and the original BPRA coalition is right to oppose this loss.

That being said, the legal requirement does not necessarily lead to labor’s positive engagement with NYPA for new projects — or their support of BPRA. At the state’s public hearing on BPRA last year, representatives from key locals of the Utility Workers Union of America and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers both spoke of NYPA’s abysmal history of actually negotiating contracts with the agency. One explained that the state’s Taylor Law prohibits public sector employees from striking, thereby eliminating the key incentive that NYPA would have to bargain.11

The BPRA coalition regularly highlights effusive praise for the bill’s labor language from one of these labor representatives — Pat Guidice, head of both an IBEW local and of the state’s Utility Labor Council. But IBEW and other unions who’d work these power sector jobs simply do not support the legislature’s bill, as their testimony last year makes clear. Instead of prioritizing these unions, BPRA’s labor support comes from unions representing teachers, nurses, university workers, service workers, healthcare workers, childcare providers, grad students, clerical workers, and museum workers of New York.

Whether the power sector unions will be more likely to support Hochul’s BPRA remains to be seen. The sad state of affairs of state labor law suggests that public ownership and financing but private construction and operations — as Hochul’s BPRA would seem to prefer — might lead to better support from and empowerment of organized labor. At the very least, these unions would need to see a new, governor-appointed NYPA executive willing to undo years of neglect and bargain in good faith.

The Road Ahead

The governor and the legislature will now engage in some dealmaking around the fate of BPRA and of NYPA’s role in the cleaner power sector of tomorrow. And, in my opinon, Hochul’s BPRA offers a better starting point than does the legislature’s.

Unfortunately, both sides are only focused on instrumentalizing NYPA to meet the state’s shorter-term, 70% renewable by 2030 target and not the longer-term, 100% carbon-free by 2040 one. Last year New York’s grid operator asserted that “dispatchable emissions-free resources must be developed and deployed at scale well before 2040” in order to make that climate target. And the wind, solar, and battery storage beloved by BPRA’s coalition aren’t that.12

By enabling NYPA to enter the renewables game long left to private industry to develop, BPRA expands the domain of public power. But by refusing to enable NYPA to enter the longer, more essential game of carbon-free power, BPRA both sets its sights too low and doesn’t offer labor unions any jobs that are not already being created in the private sector (and with favorable conditions for them).

Allowing NYPA to contract for small modular nuclear reactors, as one example of such resources, would mean offering New York unions something they’re not already seeing in the private sector. Public power entities like the Tennessee Valley Authority and Ontario Power Generation in Canada are making big bets on this advanced nuclear technology for reliable decarbonization, and smaller entities in Missouri, Nebraska, Utah, Washington (twice over), and Wisconsin are exploring it as well.

The core focus on renewables is not likely to change now that Hochul’s budget proposal has adapted that essential element. But if public power advocates want to make true progress on decarbonization that preserves electrical reliability and offers more than temporary construction jobs, and if socialists want to build stronger political coalitions with the industrial unions that actually do the work, BPRA’s original fatal flaw should be reconsidered.

Fred Stafford is a STEM professional and independent researcher on the Left. Find him on Twitter at @fredstaffordcs.

From an industry report on the program: “Land acquisition proved to be one of NYPA’s biggest challenges […]. The Authority owned none of the sites ultimately chosen for the new plants and encountered considerable difficulty in obtaining them. In a number of cases, a recognition by prospective sellers that NYPA could, if necessary, use its eminent domain powers was crucial in reaching agreements to acquire the properties quickly enough to support the ambitious project schedule. The entire acquisition process, including appraisal, negotiation of terms, surveys, mapping, and environmental test borings, was completed within three months.”

Testimony of NYPA Special Counsel Steve Kass, Assembly Energy Committee hearing, March 22, 2001, pg. 209.

There’s a lot more to say about the PM-2.5 modeling for the peakers, but that’ll have to wait for another post.

Plant selection methodology and data come from PSE Healthy Energy’s report on New York State peakers, restricted to Zone J (New York City).

“… unless the authority provides to its trustees, and makes publicly available, an attestation in writing, signed by the independent system operator and a representative of the regional clean energy hub in which the facility is located, identifying the existence of a reliability need.”

Subdivision 27-c, p. 301, of the relevant budget proposal document. NYPA “may continue to produce electric energy at any of the small natural gas power plants if existing or proposed replacement generation resources would result in a net increase of emissions of carbon dioxide within or outside New York state.”

The Center for NYC Neighborhoods is the regional hub for the Bronx and Brooklyn, which would appear to make it the deciding voice on the fate of four NYPA peakers: Harlem River Yard, Hell Gate, Vernon, and 23rd and 3rd.

Subdivision 8 paragraphs (ii) and (vi) of the proposal, pg. 300.

Testimony by Pat Guidice of IBEW Local 1049 and NY Utility Labor Council in the NY Assembly’s BPRA hearing on July 28, 2022.

Subdivision 36 of the current version of the legislature’s bill.

Taylor Act mention in testimony by James Shillitto of UWUA Local 1-2. “The worst one to negotiate with is NYPA … because they have no incentive to get it done.”

Green hydrogen combustion is an exception: a technology considered “renewable” by both versions of BPRA, and a dispatchable emissions-free resource. In Hochul’s BPRA, NYPA would be able to own and operate such turbines, and produce the hydrogen fuel. This is particularly important since NYPA has already been experimenting with blending hydrogen fuel in one of its natural gas-burning plants. You love to see public power developing new techniques.