Biden Admin v. TVA, and other public comments on TVA's Draft Resource Plan for 2025

Public comments on TVA's 2025 Draft Integrated Resource Plan have quietly been posted online. Here are some takeaways.

The Tennessee Valley Authority is deep into its 2025 Integrated Resource Plan process, after opening up a draft plan to public comments last Fall. Now those public comments are publicly available.

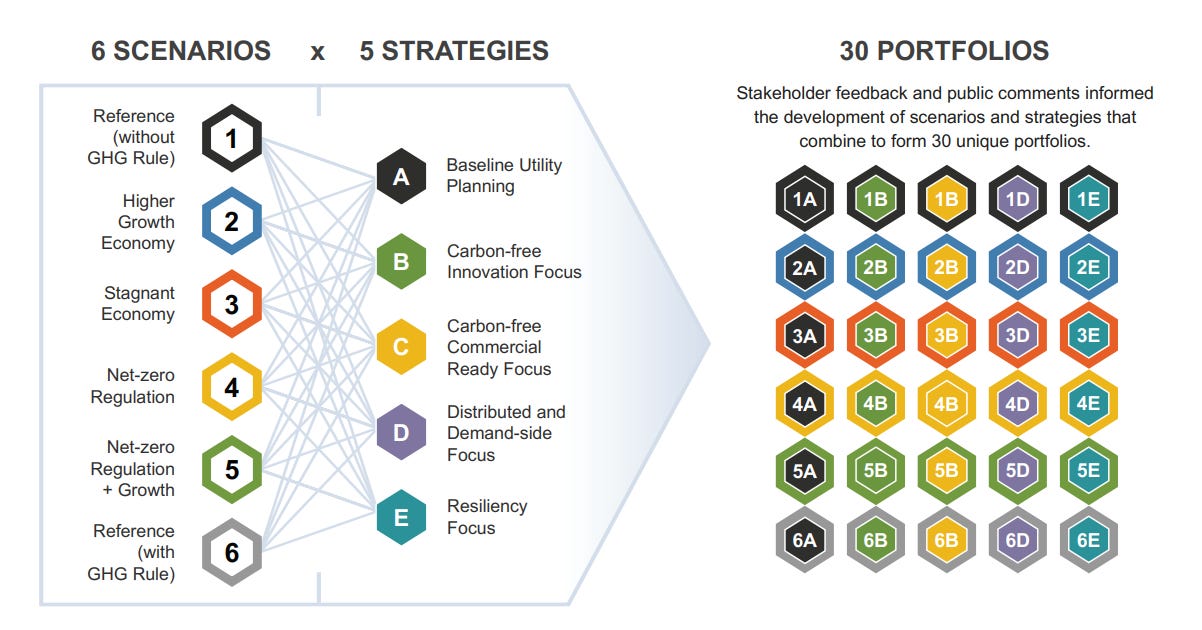

Every several years, TVA develops and publishes an integrated resource plan, or IRP, laying out the future of their energy resources. Potential scenarios they may find themselves in, political and economic, are evaluated against potential strategies that TVA may pursue.

Most utilities across the country perform some kind of IRP, by law or by regulatory order in their states. TVA is required by the Energy Policy Act of 1992 to perform “least-cost planning,” which they implement largely via the IRP. (Readers might recall I previously reported in The Nation that this requirement is part of the “Rubik’s cube” they must solve for developing new nuclear plants.) That statute says, for example, that “[b]efore the selection and addition of a major new energy resource on the [TVA] system, the [TVA] shall provide an opportunity for public review and comment […].”

In this post I’m sharing some takeaways from the public comments on TVA’s Draft 2025 IRP.

TVA’s charted strategies

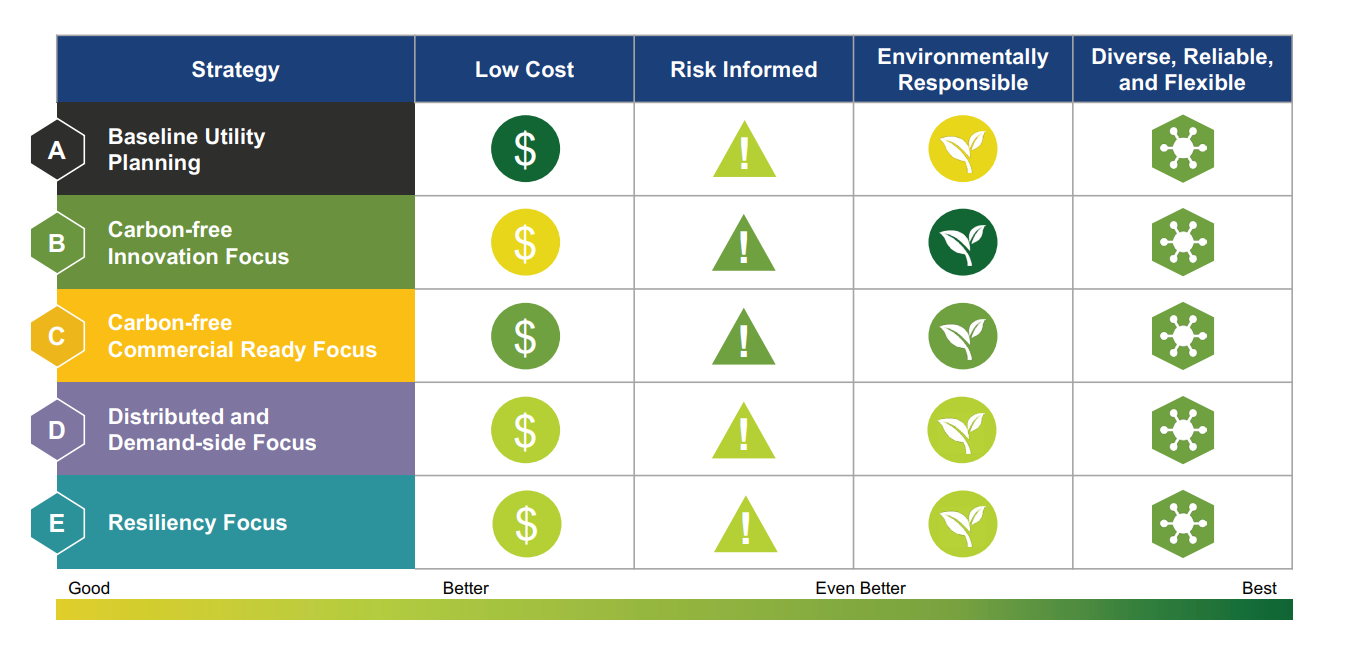

The Draft IRP lays out five strategies for how they can navigate the various risks and costs they’ve planned for, each strategy prioritizing certain kinds of resources. They are:

A, Baseline Utility Planning: what it says on the tin;

B, Carbon-free Innovation Focus: playing up riskier, advanced technologies for decarbonization like nuclear, carbon capture, and long duration energy storage, in partnership with federal labs;

C, Carbon-free Commercial Ready Focus: banking on existing commercial technologies, i.e., non-hydro renewables;

D, Distributed and Demand-Side Focus: less centralized TVA power, more decentralized TVA customer power, and more intense demand response; and

E, Resiliency Focus: smaller generating units all over the place, across various (not necessarily low-carbon) technologies, and more investment in the transmission system.

If you ask me, the way TVA can best serve its territory and the nation whose people it’s “built for” is to go whole-hog on Strategy B. With government help, TVA should be investing in the risky but necessary technologies for decarbonization, and seeing them through from lab work to operations. Of course not everyone agrees with that perspective. But what’s really striking in the public comments on the Draft IRP is that the Biden Administration did not agree either.

Biden’s EPA wants renewables, but Tennessee’s counterpart wants nuclear

The Biden Administration did a lot for nuclear power in America. But its efforts did not extend to TVA.1 Public comments from EPA—and, more damning, from the General Services Administration, in the next section—highlight just how much the Biden Administration’s stance on TVA is, effectively, renewables or bust.

The EPA is required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) to comment on all federal Draft Environmental Impact Statements. TVA submitted one alongside its Draft IRP, so the EPA decided to comment on the latter as well as the former. And what are their thoughts on the portfolio options outlined in the Draft IRP?

The EPA encourages the development of a portfolio mix that emphasizes demand-side reductions to reduce the need for power, increased development of renewable technologies, and expanded use of mitigation technologies to offset the impacts from extensive use of natural gas.

The 14-page comment, however, largely focuses on criticisms of how emissions and the social cost of carbon are modeled throughout the TVA system, and how environmental justice is concerned.

Amusingly, they ding TVA for “not evaluat[ing] the risks related to natural gas supply and the implications for grid reliability from a less diversified generation mix with a high share of natural gas generation” but of course suggest no such risks for a sharp increase in the integration of renewable energy. They also criticize some of TVA’s modeling around future policy scenarios, like around the EPA’s greenhouse gas rule finalized in 2024. They could not, it seems, foresee that a new administration would retract it.

Call me crazy but I’m not sure it should be within the EPA’s remit to dictate to TVA how it should model its energy system and which kinds of energy resources it should be prioritizing. Especially when national media treats EPA’s comments about TVA as some kind of golden truth about how to run a grid. Does anyone at EPA have to take on that critical responsibility?

At the state level, however, Tennessee’s Department of Environment and Conservation reminds TVA that it is state policy, under Governor Bill Lee, to promote nuclear energy development and asks that they review the state’s plans around that. “Additionally, TDEC supports TVA’s inclusion of Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) in the 2025 IRP,” they write. “SMRs represent a vital pathway for clean and reliable energy in Tennessee. TDEC recommends TVA prioritize partnerships and coalition-building to ensure the successful deployment of SMRs.”

Biden’s public energy buyer vs. big tech energy buyers on new nuclear at TVA

The federal government’s General Services Administration maintains federal buildings and, as such, procures the electricity that powers them.2 It’s a big energy buyer, not unlike a number of large corporations. As such, channeling the federal government’s buying power is a powerful tool of the state to promote certain industries. Christian Parenti calls it The Big Green Buy.

Under the Biden Administration, GSA signed memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with various utilities, like Xcel in Colorado, to provide 24/7 carbon-free power to its properties. One such utility was even TVA itself: the MOU between GSA and TVA would “provide DOE’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the Y-12 National Security Complex in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and potentially other Federal facilities in TVA’s service territory, with 100% locally supplied carbon pollution-free electricity by 2030.”

Going beyond nonbinding agreements, GSA even signed, in the last days of the Biden Administration, a power purchase agreement with competitive merchant generator Constellation to purchase nuclear power over a period of ten years. The contract will help finance uprates (i.e., upgrades that increase the generating capacity) at their existing plants. It was hailed as the largest-ever federal procurement of nuclear energy.

Given these gestures toward using the power of the state to purchase 24/7 carbon-free power, even the MOU with TVA itself, one would find the GSA’s comments on TVA’s Draft IRP to be quite mystifying and counterproductive:

In these comments - which were coordinated with customer agencies including Department of Defense and Department of Energy - we recommend that the Board direct TVA to create an actionable implementation plan, with next steps and milestones, clearly pursuing Strategy C (Carbon-free Commercial Ready Focus), along with supplemental elements of Strategy D (Distributed Energy Resource Focus) where appropriate.

Recall that the Strategy C promotes existing commercial technologies, i.e., renewables, basically to the exclusion of new nuclear. They note that “Strategy B [Carbon-free innovation] actually achieves the most carbon reduction benefits of any strategy TVA analyzed over the planning period.” GSA nonetheless “believe[s] that, although environmental benefits are key to the public interest, so are other outcomes – like cost.” It’s hard to argue with that conclusion, but it’s also hard to watch the state simply give up on the risky endeavor with its one (indirectly) controlled nuclear-powered utility.

It’s worth noting that they also recognize the land use problem of renewables. “TVA has also correctly noted that there are potential increased risks associated with large-scale renewable build-outs and land use requirements.” The solution? TVA should just inform the people to accept it. “Further education on the benefits and costs, and stakeholder engagement to better understand local opposition may alleviate those challenges.” Perhaps GSA should read the other public comments, described below.

Aggregating the buying power of many entities nationwide into a single political unit isn’t unique to government. Large corporate consumers of electricity like Big Tech, McDonald's, and General Motors have the Clean Energy Buyers Association (CEBA). The IRP comment from CEBA argues much the same as that of the federal government, with one major difference:

CEBA recommends that TVA model a strategy that puts the same high promotion on utility-scale solar, wind, battery storage, and long-duration storage as Strategy C but also puts a high promotion on nuclear resources. Such a strategy would likely lead to deeper decarbonization than either Strategy B or Strategy C … [emphasis added]

The private sector lobbyist mirror of the federal government’s procurement agency sees more value in new nuclear than did the Biden Administration’s executive agencies, apparently.

Many urge new nuclear, few urge new large nuclear

Many, many comments include support for TVA’s existing nuclear fleet and support new nuclear generation in general. But as far as I can tell, only three specifically urge new large nuclear, in contrast to the more commonly advocated small modular reactors (SMRs).

For the past few years I’ve been a vocal advocate for TVA to develop an AP1000 nuclear project, like the two built in 2023 and 2024 at Plant Vogtle in Georgia, as a way to kickstart American nuclear industrial capacity. Along those lines, I submitted my own comment to TVA’s Draft IRP, a largely technical comment on their overinflated cost estimate for a new large reactor:

In the Draft IRP, TVA's estimate for overnight capital costs (OCC) of Advanced Pressurized Water Reactor (APWR) nuclear technology is far higher than more recent estimates from the Department of Energy and as a result skews TVA's modeled scenarios away from this technology. Table 3-3 of the Draft IRP gives an estimate of 12,928 $/kW for OCC of APWR. But the "Pathways to Commercial Liftoff: Advanced Nuclear" report compiled by the Department of Energy's Loan Programs Office, released days after the Draft IRP, estimates that a two-unit AP1000 project, the APWR technology recently deployed at Plant Vogtle in Georgia, would have an OCC of 8,300 $/kW. TVA's estimate of the cost of new large, conventional nuclear generation is therefore 56% higher than DOE's estimate. TVA should confer with the DOE on this APWR technology and reconcile the tremendous difference in overnight capital cost estimates before continuing to evaluate the scenarios in the Draft IRP.

As far as I can tell, I’m alone in pointing out this discrepancy. But two other comments talk up the need for TVA to pursue their own Vogtle project.

Mark Kirshe of Knoxville writes that “it seems to me that the 2025 IRP is short of strong nuclear expansion, [which] is important for Tennessee and our nation to grow, prosper and reduce carbon emissions associated with expansion of burning of fossil fueled generation.” Kirshe urges “development of licensed and proven Gigawatt class BWR and PWRs as shown by the already operational Vogtle units in Georgia.”

Michael McLean of Chicago, a familiar face from X, “strongly encourage[s] TVA to prioritize the AP1000 reactor technology within the 2025 Integrated Resource Plan. … With increasing electricity demand and the need for dispatchable, carbon-free resources, AP1000 reactors represent a dependable solution, enabling TVA to retire aging fossil fuel plants without compromising reliability or increasing operational costs.”

Plenty of people hate gas, hate nuclear, hate solar, hate batteries

Name a source of electric power and people have submitted comments urging no more at TVA, except perhaps hydropower.

One form letter copy-pasted from a few dozen residents of Millington, Tennessee, demands that TVA “[k]eep solar and battery storage facilities and wind power plants on previously zoned industrial sites!” Last year the permit for a private solar farm by European energy developer RWE was rejected by the county board of commissioners as part of a new moratorium on commercial solar. That rejection was reversed after the developer sued the county, and the two sides settled. It will sell power to a Meta data center in Tennessee, with the surplus being sold to TVA. It will occupy 600 acres of 1,500 total that RWE mostly leased from landowners.

Opposition to new gas plants runs through what seems to be around half of the comments. There’s no denying the expressed sentiment is far more against gas than in favor of it. But at least a couple commenters disagree. Compared to solar, one commenter writes, “[n]atural gas works better, and the US has a lot of it. You guys do what you need. I wouldn't have known about this if it wasn't for a protest. You guys are the experts. Keep TVA profitable and the power on. Have a good one!”

Another states “I’m in favor of a natural gas pipeline. The climate is always changing primarily as a natural process. Not a climate crisis. Thank you TVA for what you’ve done for our communities.” I’m struck by both of these comments’ expressed interest in TVA itself.

Another commenter speaking in favor of gas development as an affordable path forward claims a family connection to TVA’s tainted history with coal power. “My grandfather worked at the Johnsonville steam plant and I was sad to see it decommissioned and I was afraid that it was not going to be replaced and I was delighted to see that it was replaced by a new gas power plant which is cleaner and more efficient and cheaper to sustain.” Environmentalists are misrepresenting the costs and even the effects, this commenter argues. “I know [gas] has to be a lot cheaper than environmental groups portray like evergreen action is heavily advertising against TVA's use of natural gas power plants. … Environmentalist are never happy hence this case now as they're saying natural gas is as polluting as coal production, which I'm sure is absolutely untrue.”

My own perspective on the hotly debated issue of new gas plants at TVA can be found in this post from last year.

Who’s missing from the comments?

In my report on TVA for The Nation last year, I framed the politics of contemporary public power as a conflict between, on one side, private renewable energy developers and myriad environmental groups and, on the other, labor unions and advocates for the public power model in general.

The greens of course have a handful of different organizations commenting on the IRP, from the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy to the Sierra Club. Their, ahem, partners in the private renewables industry have commented too, like the trade group Southern Renewable Energy Association.

But on the other side of that conflict there is no organization weighing in on the IRP. As I’ve emphasized over the past year, there is no advocacy organization that promotes the public power model of TVA. There are still key organizations in this camp: labor unions. For example, I reported the story that both the building trades unions and the professional employees’ union lobbied Congress to get TVA recognized explicitly as eligible for IRA tax credits.

The unions, however, are completely absent in the Draft IRP public comments. I couldn’t even find a single comment from an individual claiming to be a member of one of TVA’s unions. One person I asked about this suggested that, well, the unions just never have commented on the IRPs in the past, and nobody’s prompted them to do so.

With so many organizations and business interests promoting private power development for the TVA system, perhaps it's time for labor unions to speak up?

Notably, though, Biden did appoint some staunchly pronuclear members to its Board of Directors, like former IBEW Tenth District VP Bobby Klein and former county judge Wade White, who together comprise the Board’s nuclear operations committee.

In his brilliant book Long-Range Public Investment, historian Robert Leighninger points out that the GSA was originally the Federal Works Agency, the result of a 1939 consolidation of the Public Works Administration and the Works Progress Administration. Having presented the history of PWA, Leighninger writes of this eventual transformation: “The proud builders of the backbone of national infrastructure became the nation’s janitors.”